FPGAs

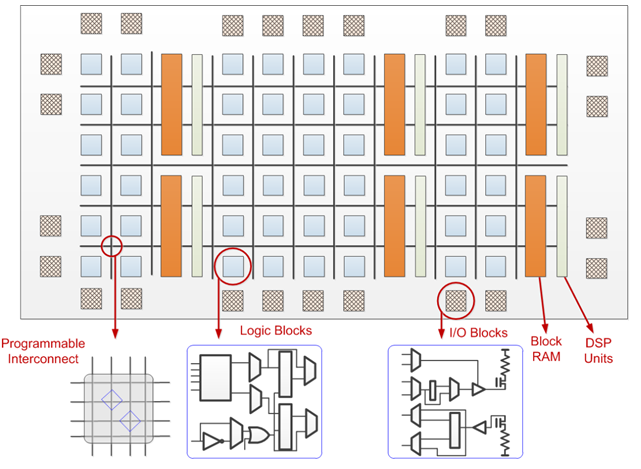

An FPGA (Field Programmable Gate Array) is a device that consists of logic elements (Look-Up Tables i.e. LUTs. Sometimes the logic elements are also referred to as Configurable Logic Block (CLB)), memory slices (i.e. BRAM) and DSP slices (Digital Signal Processor). The LUTs are all interconnected and they can be configured to behave like any logic gate. The BRAM and DSP slices are placed in-between these vastly interconnected LUTs. The “magic” of FPGA devices is that it can be configured to behave like any digital logic circuit.

Let us say, we have to design a simple 2:1 multiplexer circuit

A multiplexer is a switch in essence that is quite helpful in digital circuits to dictate the inputs to certain blocks. It operates the same way a relay switch does. A 2:1 multiplexer has three inputs and one output: two inputs which need to switched between, one input to select which input to switch to and one output that connects to the selected input.

The SystemVerilog code for the 2:1 multiplexer looks like this:

module mux21 (

input logic in0, // Input 1

input logic in1, // Input 2

input logic sel, // Select line

output logic y, // Output

);

assign y = sel ? in1 : in0; // Ternary operation -> if sel is 1, y = in1 else y = in0

endmodule // mux21

The typical FPGA has a set number of LUTs, BRAMs, DSPs and IOs. Although these are set, they are still too many to be configured by a human and hence require some heuristic algorithms to configure the hardware described in your source file (mux21.sv in this case). An EDA (Electronic Design Automation) tool comes to the rescue here and does all the tedious configuration and optimizations for us.

The source file is linted, compiled and then synthesized (i.e. mapped to the resources on the FPGA, in this case). The EDA tool performs various operations (floorplan, routing etc.) to ensure correct and efficient use of the FPGA resources.

The above image is a mux inferred with logic gates. Now, like I mentioned before, the LUTs can be configured to behave like these gates. The EDA tool generates a binary file called the bitstream that is sent to the FPGA. This bitstream is essentially an image to be configured onto the resources on the FPGA.

The configuration all depends on the circuit’s truth table (to put it simply). Once the boolean equations of the circuit have been optimized by the tool, the LUTs are configured accordingly to behave like the circuit defined.

Read more about LUTs here

So, what are BRAM and DSP slices?

BRAM and DSP slices are special blocks embedded within the FPGA fabric. Let us get a brief understand about these blocks:

Block RAM : A volatile memory element on-board the FPGA to help with storing data closer to the CLBs.

DSP block : A Digital Signal Processing block has fast adders, multipliers and other potentially parallelizable to perform DSP operations like FFTs (Fast-Fourier Transforms, Number Theoretic Tranforms etc.) If your design contains arithmetic blocks, the EDA tool will assign these operations to the DSP slices to both save on CLB/LUT real estate and improve performance.

An FPGA seems like the perfect device for developing hardware, but what is the main concern?

The main concern is the time it takes to configure an FPGA. Modern computation now happens at gigahertz speeds, but when configuring an FPGA, we have the EDA tool performing largely heuristic and hence non-constant time computation and then forwarding the bitstream to the FPGA. Not ideal if we want “dynamic” hardware.

What do I mean by dynamic hardware?

To set the premise, I am highlighting the possibility of having an FPGA that can reconfigure (itself) during runtime, hence making it “dynamic”. Having dynamic hardware can change the way we design systems. Imagine having an FPGA accelerating a workload like real-time ML inference and it is scheduled to perform another workload up next, and let’s say it has the ability to reconfigure itself that would be the best way to reuse your compute and still get high throughput while keeping power consumption lower than GPUs.

What I am about to discuss up next is still mostly in theory and not yet in practice so the majority of the next section can be taken as speculation and brainstorming.

Runtime Reconfiguration of an FPGA device.

The Xilinx FPGAs we have now have tons of resources to use and even have multiple FPGA fabric regions called SLRs (Super Logic Regions).

Now, imagine being able to use these SLRs to independently run individual workloads or even smaller parts of a larger workload. Since FPGAs are mainly used for acceleration due to it’s inherent property of leveraging, what I would like to refer to as, awkward parallelism. This idea to utilize the SLRs to perform different computations has not been widely explored and hence seems like a worthy topic to pick up if you are intrigued to develop something on this.

Runtime reconfigurability however has been explored numerous times in the academic space. We need to know that FPGAs often come packaged with a soft-core or a simple CPU to perform some operations to aid the FPGA fabric and the possibility to use these CPUs to possibly dictate the reconfiguration was discussed in these findings.

Some advantages of runtime reconfigurability:

- Efficient usage of FPGA resources.

- The potential to have your hardware adapt to the workload demands.

- Power utilization is theoretically lower.

We saw that the configuration of the FPGA takes a bit of time, but we did notice that the EDA tool outputs a bitstream file that holds the configuration for the FPGA fabric. This gives us an idea about how we can pretty much precompute these bitstreams and have them on the RAM of the FPGA device (not to be mistaken with the BRAM slices but an actual DRAM module with the CPU). Now that we have the bitstreams of different designs (let us say we have one design for ML inference and another to accelerate a genomic analysis workload), all we would need to figure out is how we do the configuration on the board dynamically, right? Only if it was that simple.

The process of computation is not that straight forward for the majority of the workloads, we cannot possibly know what’s the best way to schedule these reconfigurations during runtime without having the throughput drop. Most of these workloads are dynamic and dependent on the inputs and hence are never commonly constant-time.

Let’s say we are optimistic that we have two contiguous processes that need FPGA acceleration and don’t have any dependency and all computation is constant-time. Realistically, how much can we benefit from reconfiguration during runtime for such workloads? I suspect not much because, we are precomputing the bitstreams and these are going to be fixed hardware (not parameterization) and I am sure there would still be a marginal boost in performance but why would an architect do this when they can deploy another FPGA at their disposal for the subsequent workload?

In this, they have discussed the possibility of having partial reconfigurability of the FPGA fabric. If this is possible, this would mean that we can leverage almost all the resources on the FPGA effectively while having the ability of have dynamic parts in the system. The problem would be that it would take extra time to compute partial configurations since the number of FPGA resources now is not known until the previous configurations happen and hence the bitstream generation cannot be performed in parallel.

Tons of problems with having runtime reconfigurable FPGAs, what might be the solution?

The time taken by the EDA tool to perform heuristic analysis of routing and floorplan is the highest during the bitstream generation. If we can figure out, how we can potentially handle this, we can have runtime reconfiguration as a feasible solution.

This paper discusses the ability to segment workloads down to “epochs” and hence have an interconnect that essentially performs dynamic reconfiguration for each epoch of computation. This solution aims to alleviate the large context switching overhead since the arbitration and reconfiguration is happening within the FPGA fabric.

This pre-print discusses another unique approach to enable runtime reconfigurability by basing the reconfiguration parameters from the inputs.

I would like to see if one can leverage the multi-FPGA fabric regions (SLRs) to split up computation and workloads and even have the ability of configure each SLR during runtime. There is some evidence on being able to configure the IO for each SLR. This seems promising and the possibility to implement the idea of multi-workload on a single large FPGA across it’s SLRs is looking realistic.

Potential problems to tackle

- The design cycle will not be as straight-forward hence it would take more time to develop an effective system to run on the FPGA.

- There are concerns with side-channel attacks and memory leaks across SLR bridges. Although there are mechanisms to mitigate attacks, these might cause undesirable overheads.

- We might need to design intermediate blocks to hold and forward data to and from one SLR to another, this might be tricky as we have to be able to accomodate arbitrary data widths and be able to schedule them on time between SLRs.

So, in the future we will have dynamic hardware then?

The advancements in computation has been exponentially trending up and I see the possibility of FPGAs playing a large role in laying the foundation for the next generation of computers that can dynamically reconfigure themselves. It would not be fair to not mention about LLMs in this case. Although I am not the biggest fan of the trend, I do understand the impact that LLMs have done. It would be safe to say that LLMs too will play a huge role in having smart, dynamic computation since regular heuristic algorithms just don’t cut it. LLMs can be the little bot steering the computation on the FPGA. Intriguing times ahead!